Hornos de la Peña es un yacimiento emblemático de la Prehistoria de la región cantábrica. En 1903 Lorenzo Sierra descubrió en la cavidad grabados paleolíticos. Desgraciadamente para entonces el yacimiento que se encontraba en la entrada de la cueva había sido casi totalmente destruido. Entre 1909 y 1910 Hugo Obermaier dirigió una excavación en el pasillo inmediatamente posterior al vestíbulo, revelando una secuencia de 3 niveles arqueológicos (III- Musteriense; II-Solutrense/Auriñaciense; I- Magdaleniense) que sirvieron para definir la secuencia paleolítica de la región cantábrica.

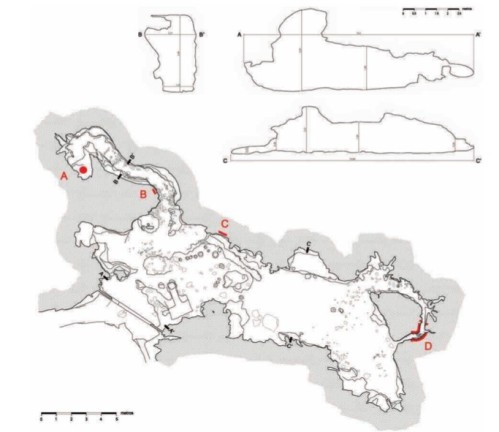

El yacimiento y sus materiales fueron posteriormente objeto de la atención de numerosos investigadores, entre ellos Lawrence. G. Straus, Federico Bernaldo de Quirós, Pilar Utrilla o Elena Carrión. Sin embargo los problemas de la secuencia descrita por H. Obermaier, las dificultades para datar las distintas ocupaciones y los avatares sufridos por los materiales desde 1910, habían relegado al yacimiento a un segundo plano frente a otros yacimientos como El Castillo o Cueva Morín. Sin embargo, en el año 2008 Hornos de la Peña se incorpora junto a otras cuevas de la región cantábrica a la lista de Patrimonio Mundial de la UNESCO, por la singularidad y riqueza de su arte rupestre. A principios de la década de 2010 se retoma el estudio de la cavidad por un equipo dirigido por Olivia Rivero. Este estudio tiene como objetivo abordar la revisión del conjunto artístico incluyendo una nueva topografía y una documentación gráfica actualizada (Rivero y Garate, 2013). Uno de los objetivos es el de demostrar la existencia de dos ciclos artísticos diferenciados (uno de inicios del Paleolítico Superior y otro Magdaleniense) y tratar también de contextualizar una pieza grabada recuperada en la excavación de Obermaier que se había puesto como ejemplo del primer arte auriñaciense de la región cantábrica (Tejero et al., 2008). En este contexto se inició un proyecto integral de revisión del yacimiento, que incluye desde el año 2016 la excavación de los testigos dejados por H. Obermaier y por los fosfateros en el vestíbulo y en el primer tramo de la galería principal de la cueva. Los primeros trabajos sobre esta secuencia acaban de ser publicados en la revista Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports (Rios-Garaizar et al. 2020).

La reexcavación de la sección preservada por H. Obermaier en esta zona de la cueva ha servido para volver a evaluar la propuesta estratigráfica que se ha mantenido en vigor los últimos 100 años. Los nuevos datos indican que, a grandes rasgos, la lectura de H. Obermaier fue correcta pero la secuencia es mucho más compleja que la descrita originalmente ya que frente a 4 niveles descritos por H. Obermaier nosotros hemos identificado al menos 15 unidades estratigráficas que abarcan desde el Pleistoceno Medio al Holoceno. Aunque hemos tenido problemas para identificar claramente la posición estratigráfica del Solutrense y del Auriñaciense hemos puesto de relieve la presencia de otros momentos de ocupación.

Son especialmente importantes las ocupaciones magdalenienses que se dan a techo de la secuencia (unidad 4) y que hemos datado en 13,790 ± 60 BP (OxA-36543), fechas propias del Magdaleniense Medio de la región. En este nivel se ha recuperado abundante fauna y restos de industria fabricados en sílex, entre los que se han identificado variedades como Monte Picota, Flysch, Treviño y Urbasa.

En el conjunto de unidades 5-12, que deberían corresponder con el nivel II de Obermaier (Solutrense/Auriñaciense), hemos identificado una unidad muy alterada (5) que ha proporcionado una datación idéntica a la de la unidad 4; otra unidad afectada por madrigueras (6) que hemos datado en 22,470 ± 140 (OxA-36545) que se corresponde con el final del Gravetiense o el inicio del Solutrense, y que ha proporcionado un escaso conjunto de industria lítica, una punta de asta y una cuenta fabricada en marfil; una serie de unidades fluviales (7-12) que han sido datadas en 25,120 ± 19 BP (OxA-36546) (Unidad 8) y que han proporcionado un exiguo material arqueológico que incluye unos pocos restos de fauna, algunas lascas y laminillas y un fragmento de azagaya de asta

Sin embargo la unidad más interesante ha sido la 13, que ha podido ser excavada en una mayor extensión. En esta unidad se ha recuperado un numeroso conjunto de industria lítica y fauna asociado a un hogar parcialmente desmantelado. El conjunto lítico está fabricado en distintas variedades de cuarcita y sílex (Monte Picota y Flysch) siguiendo esquemas de producción discoides que han generado abundantes puntas pseudolevallois. Estas características permiten vincular este nivel con el Paleolítico Medio regional de El Castillo, La Pasiega, La Flecha o Cueva Morín. Por debajo del nivel 13 hay otras dos unidades, de las cuales el 14 ha proporcionado escasos restos de fauna muy alterados. Estas unidades se disponen sobre una espesa costra estalagmítica que ha sido datada en 222,920 ± 10,090 (JRG-11.17).

Los trabajos arqueológicos en Hornos de la Peña aún no han concluido. Entre 2018 y 2019 hemos ampliado la excavación de las unidades 12-14 y hemos refrescado uno de los testigos conservados en el vestíbulo de la cueva. Estos trabajos están poniendo de relieve las ocupaciones del final del Paleolitico Medio e inicios del Superior y sin duda serán de gran importancia para tratar temas como la desaparición de los neandertales en la región cantábrica o la llegada de los primeros humanos modernos.

Referencias:

Rios-Garaizar, J., Maíllo-Fernández, J.M., Marín-Arroyo, A.B., Sánchez Carro, M.A., Salazar, S., Medina-Alcaide, M.A., San Emeterio, A., Martínez de Pinillos, L., Garate, D., Rivero, O. (2020). Revisiting Hornos de la Peña 100 years after. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 31, 102259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102259

Rivero Vilá, O., Garate Maidagan, D. (2013). Arte parietal Paleolítico en la cueva de Hornos de la Peña (Cantabria): nuevos datos sobre su conjunto exterior. Zephyrvs, 72, 59-72. doi:10.14201/zephyrus2013725972

Tejero, J., Cacho, C., de Quirós, F. (2008). Arte mueble en el Auriñaciense cantábrico. Nuevas aportaciones a la contextualización del frontal grabado de la cueva de Hornos de la Peña (San Felices de Buelna, Cantabria). Trabajos de Prehistoria, 65(1), 115-123. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.3989/tp.2008.v65.i1.138